#156 | Mythical Yugoslavia

Belgrade, Serbia

Yugoslavia collapsed in 1992. Even so, last week I was sitting with a Bosnian coffee close to Trebevic Peak, which squats above Sarajevo; my friend Murat shouted to the cafe owner, “Are you from Bosnia-Herzegovina?” — “yes…” , he said, with distinctive reserve. Murat responds, “or Yugoslavia?” “Ah! Yes!!” calls his reply, and then, in heavy Bosnian, “…long live Yugoslavia!” Živjela Jugoslavija!

Every country has a myth. Uniquely, the ex-Yugoslav nations have a shared one: Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia delivered a Third Way, an alternative to American capitalism and Soviet communism. While there was economic mismanagement, restrictions on press freedoms, and the final tragic state dissolution, a prosperous Yugoslavian image today captures the minds of the Balkan peoples. The Yugoslav story captures my imagination, too. Yugoslavia still invites us — as mythic as it now is — to imagine alternate ways to live and envision a world where our efforts support others. Therefore, the Tito memorials, his framed portraits in sitting rooms, and the epic Yugoslav infrastructure (indicative of frivolous spending) point at better ways to live; a path without gulags, yet with socialised healthcare and education, with employee autonomy and collective decision-making.

The Yugoslav bloc’s strength, independence, and courage cast a glowing shadow over almost every interaction I have had in Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Serbia. And it begs the question, what was so great about this historical country? Why do so many dream of a return to Tito’s Third Way? How was a country of 23 million people across six republics so dominated by the image of one man, Josip Broz Tito? He was neither in power at the creation of Yugoslavia nor alive when it collapsed, yet Yugoslavia is his country, and his memory captures it. These are the questions that have occupied me in the last week and ones I’ve tried to, from my saddle, come to terms with. They are not, I should add, small questions. Nor, because of the retina-blinding nature of hindsight, are they perhaps answerable.

But let’s begin with a quote from Tito himself: “…young people en masse began declaring themselves as Yugoslavs. It was a form of rising Yugoslav nationalism, which was a reaction to brotherhood and unity and a feeling of belonging to a single socialist self-managing society. This pleased me greatly.” Tito, I think, was right to be pleased.

Today I am writing from Flat Cafe, in Belgrade. It has dark red walls, scattered faux-mahogany tables and chairs, and the wooden windows are spread open to welcome the daybreak from Kneginje Ljubice street, the equivalent of London’s Broadway Market. It’s the cool bit.

My god, this city has good vibrations. The streets are clean and flush with beautiful people, the bars are open all day every day, and the coffee shops close at 11 p.m. Every cafe crosses the inside-outside barrier, with people sitting out in the street and around the coffee bar; people chain-smoke inside. Serbs, I am told, spend their rent on beers for their friends. When I am with a Serb, they refuse to allow me to pay. I am their guest; I am told their honour is at stake, not their money. The city’s centre is definitively Austrian in design, is temperate, and sits on two rivers, so you are never far from water (this is good for the soul). I am never hungry, as every third shop serves a slice of fresh pizza for 130 Serbian Dinars, so about £1. And I keep meeting young, wise Russians who sadly can’t go home because of their brave opposition to the war — they are rebuilding their lives here (Serbia is one of the few Russia-friendly countries, partly because of the Orthodox Church).

Whatever has a past has a myth, though history is obscured through the smog of hindsight as a morning mist hides a country lane. Nations carry myths which bind societies — or blind them to wedge them apart. Myths are reinforced in school textbooks, shared over familial roast beef, tweeted, and published as press headlines. These mythic stories alter our futures: They are the foundations on which our fates are stacked. Each of us carries a personal myth (we do well to be aware of it). Imagine ever-widening concentric circles; our myths sit between neighbours and exist as villages, towns and nations. The legends of our countries, which are more-or-less shared by the population, are of generational significance. We fight wars for them. Sometimes families are torn apart — frequently limb from limb — in service of them. Yet, like mortar in a crumbling wall, they also bring communities together.

Each Balkan state has its myth aligned with religion (to historically devastating effect). However, there is now a shared myth grown like a flower from the seeds of history. Speaking to Serbians, Croatians and Bosnians in the last fortnight, I have, without exception, been met with unbounded exuberant smiling and nodding whenever I have mentioned Yugoslavia. The country existed from 1918 to 1992 and was founded as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes after the First World War. It was an astonishing achievement. It brought about security and an increase in living standards. Most importantly, after two decades of unstable leadership, Tito came to power in 1943, transforming the country into the relatively liberal communist state we remember. Today, it feels like there is no alternative to democratic capitalism. Yet Tito’s Third Way offered another path that trod the thorny geopolitical path between the USSR and Pax Americana. Yugoslavia prospered for decades but eventually collapsed. Their myth endures as a utopian ideal enjoyed for decades by the Yugoslav people.

Security & religion

The first job of a state is to keep people safe. A safe people can work, be educated, grow an economy, and develop a culture. In the absence of safety, citizens cannot plan their futures, invest, or trust. As we can see in too many parts of the world a weak state means economic devastation: In Syria, real GDP is projected to contract by 3.2 per cent this year; Afghanistan has had an average annual growth rate of -5.4 per cent over the last four years; the UN classifies Somalia as the world’s least developed country. (One case for America’s economic dominance is its vast oceanic borders, which make invasion impossible.) For hundreds of years, the Balkans have been caught between warring empires. The Romans, Greeks, Ottomans, Austro-Hungarians, Russians and Germans have each invaded. Until Tito, the Balkans never developed the internal solidity to exercise independence and enjoy lasting peace. By contrast, Yugoslavia was a profoundly independent state and refused to become a puppet to the USSR. Stalin and Tito’s relationship deteriorated in 1948, and the country looked west, gently liberalised, and remained communist). During Yugoslavia, safety was enjoyed from external threats by sitting between the USA and USSR, un-aligned and therefore a potential ally to both.

“I am the leader of one country which has two alphabets, three languages, four religions, five nationalities, six republics, surrounded by seven neighbours, a country in which live eight ethnic minorities.” — Tito.

Tito was acutely aware of the range of peoples and interests within the Yugoslav borders. The defining differing characteristic of the peoples is their faith. Simplistically, religious differences explain many conflicts in the previous two centuries. Across the different nations, language is broadly shared, as is diet and culture. However, on my bicycle, I have visited the towering minarets of Sarajevo’s mosques and wandered under the vast blue Orthodox Temple of Saint Sava, which dominates the Belgrade skyline. I have cycled past countless small Roman Catholic churches in Croatia with their quiet congregations. Although Tito was Croatian, he only identified as a Yugoslav. And no church — not the Orthodox Serbs, not the Jews nor Muslims, nor the Croat Roman Catholics — had the right to influence the state. It was a communist secular country. However, people had the right to be religious. There was religious freedom, and no religious groups dominated one another. The leadership of Yugoslavia was above and beyond religion, allowing for internal peace. The conflicts preceding and following Yugoslavia are a testament to the successful and delicate management of religious freedoms.

A new economy

Late one evening, tired and hunched over my handlebars, I sulked into Tuzla in the deep blue darkness, rolling under the expansive power plant cones that made everything, especially me, seem vanishingly small. The roads were empty, and the moon was obscured by metallic clouds that climbed from the power plant as if escaping hell. Tuzla is in the north of Bosnia-Herzegovina and is perhaps its most pluralist city. Sitting with my friend Amir, fuelling on beans, meat, and tea, I ask about the perception of Yugoslavia. He points out that vast infrastructure was built and socialised under Tito. Croatians drive on Yugoslav roads, Bosnians attend Yugoslav universities, and Serbs take Yugoslav trams, which cut between Yugoslav apartment blocks defaced with modern graffiti.

And he was right. The plant I had cycled past was Yugoslav. Last week I visited Tito’s secret nuclear bunker, the third most significant infrastructure investment in Yugoslavia, costing the equivalent of $19 bn in today’s USD. Tito never used or visited it. Even knitting my route between towns, I often pass historical (and derelict) projects: Concrete transmission towers are buried on ridge lines like an alien ship might have landed. The levels of infrastructure development, which was state-funded (often with debt, but more on that later), have not been seen since. Seeing daily the artefacts of a prior (heavily industrialised) state builds the myth of the economic dominance of the preceding country. Yet, that dominance was short-lived.

Our myth deviates from reality when we explore the economic stability of Yugoslavia. I have heard stories about how everyone had work and that people’s summer holidays were state-funded. Yet the nation’s collapse was sparked by its weak economy. While there was undoubted modernisation, this was a global miracle, not uniquely a Yugoslav one. Having a television at home was rare at the end of the Second World War. In fact, in 1945, fewer than 10,000 televisions were in the United States. By 1960, more than 60 million TVs had been sold. The dissemination of technology from science fiction into people’s homes was an arching story of the twentieth century, and Yugoslavia was also a beneficiary.

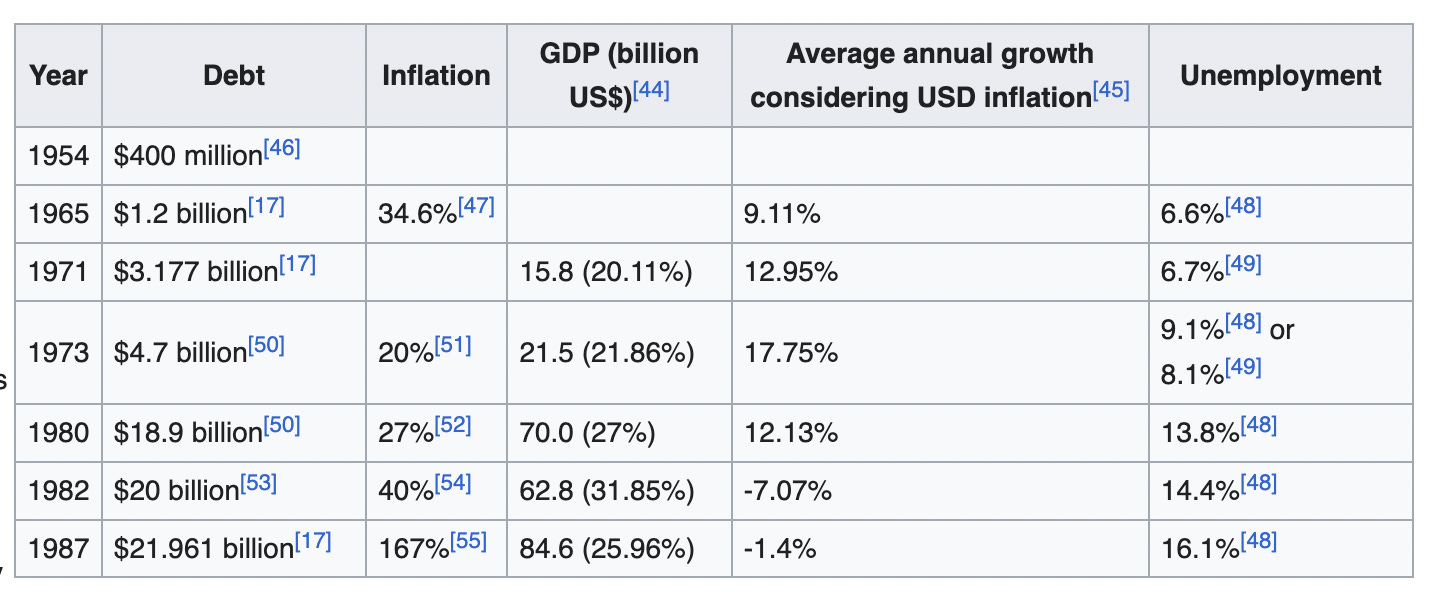

Economic development is, however, expensive, and the centralised management of the economy was ultimately unsuccessful. Yugoslavia borrowed billions from the West (especially from the United States) from the 1950s onwards. Social security expenditures increased six-fold in the 60s and 70s. Even though Yugoslavia’s debt was only 20% of GDP in 1971 (at the time, the UK’s was 68%), it faced issues with unemployment and inflation. Briefly: unemployment was 13.8% in 1980, not accounting for the one million workers employed abroad; a further 20% were under-employed. The official workweek was reduced from 48 hours in 1963 to 36 in 1970 to combat unemployment. As you can see in the table from Wikipedia, inflation was consistently high, and although there was annual GDP growth, inflation reached 1,000% in 1989(!!). It proved impossible to manage the economy, and it eventually failed.

Innovation

Yugoslavia was truly innovative. It took the principles laid down by communism and exercised them without the harsh violence of Stalin’s USSR. Yugoslavia’s third non-aligned way kept its citizens safe and allowed creativity to flourish. Notably, for a dictator, Tito was benevolent (albeit one appointed for life). And in this capacity, perhaps also because it was prohibited to criticise him openly, there was a cult-like adoration of the figure which united and maintained the southern Slav peoples. Moreover, for his myth, his death was perhaps good timing. As we have seen, it was only after 1980 that the economy began to crumble. He oversaw a period of economic stability and growth that had not been seen in the region in living memory. Before Yugoslavia, there was tragic violence. After Yugoslavia, again, violence. Relative peace, security, and growth persisted (even if it was not as golden as it might appear with such luminous hindsight).

A grain silo

I have only taken one route through these countries, spoken to a few dozen people, and read a few books. There are likely embarrassing gaps in what I’ve portrayed. But, just as a dissectologist1 has to place their puzzle pieces before nightfall, I am now leaving Belgrade and heading south through Serbia (the landscape gets more mountainous, the forests denser, the wild dogs wilder).

Yugoslav communism was a utopia but ultimately an unsustainable one. The cavernous grain silos in Belgrade are now ‘Silo’, a club with choice vibes and acoustics. I stood there, soda water in hand, reflecting on the beautiful circular irony of international loans building communist infrastructure, which is now — long redundant — full of international tourists taking pills. We have one solace: the rise and fall of empires entertains tourists at every stage of the roller coaster. The value of the Yugoslav myth remains, however: It is demonstrably possible to enjoy collective peace and sustain economic growth in the Balkans.

I think, even more importantly, the myth reminds us should continue to dream of alternatives to how we live: Were you born to be a sausage in the capitalist sausage machine? Were you, of all people, created by whatever god from the putty of the infinite to generate Lifetime Customer Value or fulfil business plans? Are you just an inadequate row in Excel? An unlikely IF function? Call me crazy, but I think you are better than a premeditated consumerist boolean; you deserve more than being force-fed ads for eighty years only to buy a pre-calculated percentage of them. Cold hard capitalism is not the answer — Yugoslavia’s myth reminds us.

*

Live well,

Hector

‘A dissectologist is a person who has a passion for solving jigsaw puzzles, and derives great pleasure from the process. This term originated from the wooden dissected maps that were popular in the 19th century.’