Niche

Being niche isn’t cool. Warhammer is niche, as are Vipassana’s and as is swinging. Niche is bucketed with kinks. Most niche things are unusual, and done either alone, or in silence, or with masks on. Yet when starting anything—especially a business—being niche may well be the greatest hack of all. The following story is my own: A tale of tragic misguided optimism.

I’m interested in the product/market fit question. It represents a watershed moment for Yokeru. Thiel says a startup is “a small group of people that you’ve convinced of a truth that nobody else believed in.” Having product/market fit is proof that strangers also believe the truth you’ve discovered.

In the last eighteen months, we’ve built a business that helps people get care when they want it, not after they’ve deteriorated (and subsequently fallen). I rarely underplay the potential for improving the care system in the UK, and later globally.

Today, we are on the brink of understanding the wide potential impact of Yokeru (we’ve supported 30,000 people, but the potential is 10,000x this—at least…). However, we haven’t always been this close to knowing—in fact (as a dear friend often reminds me), we nearly quit 9-months ago.

Things were not vibrating.

The story starts February 2020. We began extremely niche (not kinky): as a calling tool for local authorities to use in crisis. Yokeru became a pandemic product. Fantastic early traction meant our idea (and our ego’s) ballooned. With them, our optimism thrived. As the months ticked by, the immediate vision grew from a tool for one specific customer (a British local authority), to a platform for all organizations globally.

While still bootstrapping, in three months the team grew to seven, we had a fancy office in WC1, and we were launching in the States, submitting bids for government work in Australia, and having partnership conversations in Singapore. We were featured in the Shropshire Star for goodness sake. Few were in doubt that the Alexander brothers, and the wider team, were going to the moon.

Yet the megadeals weren’t landing, and I was unsure what to put on our website. “Identify unmet needs”? “Automated call centre”? “Deliver payment reminders”? “Badger your ex with morning calls”? We could do a lot—but we had not chosen which thing we wanted to do. We hadn’t even asked ourselves where we could make an impact. Where was the fulcrum? We had more verticals to approach than customers in each vertical. It was ridiculous. Momentum and morale waned.

As the grandiosity of our idea grew, with it the chance of getting to product/market fit slipped from our sweaty palms. (They were getting very sweaty, too.) All of the conversations, all of the excitement, all of the noise, meant we couldn’t see a clear route forward for Yokeru. Moreover, we became too busy to think about the best route forward. It became time for inherited advice: My father used to read me Kipling, and some lines stuck with me.

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

No one was blaming me, but I had been responsible for fucking it all up. It was at the peak of the idea grandiosity when we hit rock bottom: the noise was deafening. Money was running tight, moral was low. It was time to slow down and listen hard for good vibrations.

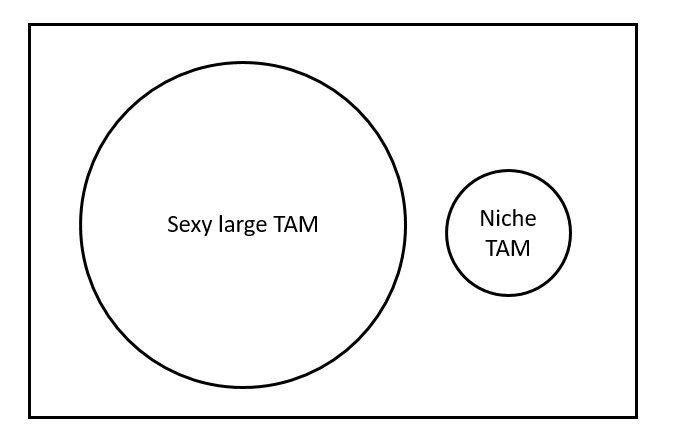

In startups, there are three constraints: time, money and energy. They are linked. As time passes by, without traction, energy dissipates. As cash crunches, and morale runs low, founders often find themselves growing the vision (and the Total Addressable Market, or TAM), to keep up the psychological momentum and appease concerned investors. Moreover, this leads to grandiose visions that are counterproductive to reaching product/market fit. After all, who wants to go after a TAM that’s less than £10m, as ours is? But it’s a good thing.

The problem with having a small TAM is that the company becomes unattractive to investors. VC’s look at businesses with a clear path to $100 million annual revenue—a number that’s unthinkable even over a decade in our current niche. Moreover, who want’s to work for a company that’s operating in such a small market?

So here we’re going to explore a virgin concept: Immediate TAM.

Immediate TAM allows startups to keep their large TAM intact, while focusing down on a sub-set of the larger market for immediate conquering. If the Immediate TAM is too big (like ours was—it was huge), then it’s an indicator that the ongoing experiment is too broad. Answers will be hard to hear. If we look at the above image another way, we can see that each market opens the door to the next (it’s logical). So the market is not big today, perhaps, but it will grow at some point in the future.

Cicero said ‘Everything has a small beginning.’ All startups start small: as a napkin and an idea. Remembering this truth every day grounds big ideas. It zooms into the problem that is being solved. Amazon routinely exercises this level of focus. Jeff Bezos, in his Letter to Shareholders in 2016, comments:

“Staying in Day 1 requires you to experiment patiently, accept failures, plant seeds, protect saplings, and double down when you see customer delight.”

I read this as Day 1 being picking a small market and experimenting. The Immediate TAM is the one that one should be gone for on Day 1—which is every day.

Back to September last year, the noise was deafening. Rumi said ‘The quieter you become, the more you can hear.’ So we went silent, restructured the company (management consultant speak), and moved to Istanbul. We continued conversations, iterated on the product, and dug deeper into what problem we could solve. Peter Thiel’s words reverberated around my head:

‘Every monopoly dominates a large share of its market. Therefore, every startup should start with a very small market. Always err on the side of starting too small. The reason is simple: it’s easier to dominate a small market than a large one.’ We went looking for a small market—where no one else was looking.’

The difference between a grandiose vision and a niche one—which has a small Immediate TAM—is not the ultimate outcome, but the appreciation of the stage the team is at. Such a niche forms part of the journey, but it’s absolutely necessary to identify it, identify the players in it, and go after it with the focus of a dog on a bone. Amazon deploys a 2-page press release strategy for every new business venture. It’s not a mere corporate exercise, but an exercise for deep thought. It forces answers to: What is the product? Who will buy it, and why? What is the Immediate TAM?

We haven’t yet reached the conclusion of the Yokeru story (there may never be a conclusion. Just chapter after chapter arriving in your inbox every Sunday). However, I’m confident we have a niche: a sufficiently defined market to grow into. The only job to be done is keeping focused on it. If we fail to do this, then we’ll be back in the wilderness of grandiose ideas, with the racket that comes with it. This is why I’m writing you this email—for accountability.

Shortly after I published the essay on being pre-product/market fit a friend asked ‘heck, Hec, you’ve said trust in the process—but what’s the process?’. I’ve outlined it here: find a small Immediate Total Addressable Market, write a 2-page press release, and go address it.