On free will

If you and I have spoken in the last few months, you’ll have heard me mention free will. It’s liberating to realise our perception of free will is an illusion. Today, I thought I would write down the case against having free will. It has broad implications for our society.

Free will is something we take for granted. It makes us into us. We feel like it was ‘me’ that made that big career move, called the top of the market, and spoke-up when someone was mistreated. On some level, our existence is given its meaning by the actions we feel like we take. If I study hard and get into a great university, I think I have indeed determined my path.

I am responsible for my success! I might shout.

However, this is not as it seems. You can no more put the success of your life (or failings) down to free will as you can take responsibility for being born or having two ears.

Free will is a cultural phenomenon. Unlike all prior civilisations (Indian, Roman, Chinese), we believe that fate comes from ourselves. In German, ‘wird, the old-English word for fate, evolved to werdung (to become), and later, in Jungian psychology, it became Menchwerdung. Menchwerdung is the process of individuation. It’s ’the process by which a person becomes a psychological individual, a separate indivisible unity or whole, recognising his innermost uniqueness, and he identified this process with becoming one’s own self or self-realisation, which he distinguished from “ego-centeredness” and individualism.‘. The concept of free will has since conquered our world.

We define free will as the 'power of acting without the constraint of necessity or fate; the ability to act at one’s own discretion.’ While I agree that we exist outside of determined ‘fate’, our ability to act at one’s discretion is an illusion. There are two arguments for this.

The first is that almost every influential thing that happens to us in our lives is entirely outside our control. Path dependence is when the decisions presented to people are dependent on previous decisions or experiences. These former decisions, too, were subject to path dependence (and back it goes!). It features heavily in economics and social sciences, explaining why a feature of, for example, today’s economy exists not because of current conditions, but from a sequence of past actions.

We face decisions that are subject to path dependence in every moment of our lives. We have no control of the route of the path (although it feels like we do). We don’t decide to be born healthy or grow up in the UK. If the decisions we make (the ability to ‘act at one’s own discretion’) rely on such gifts, do we have free will? Of course, we don’t.

Second, our brain is like a madman, gibbering on with thoughts that we have no control over. If you wrote down every idea that comes to your mind and published it as an e-book, you’d be incarcerated. We have no way of controlling how we think. We may be able to point the flashlight of consciousness in one direction or another for a moment, but it invariably returns to some unhealthy loop (for example, I still think about smoking more than I should).

If we have no control over our thoughts, and our actions are thoughts manifested, how can we control our actions?

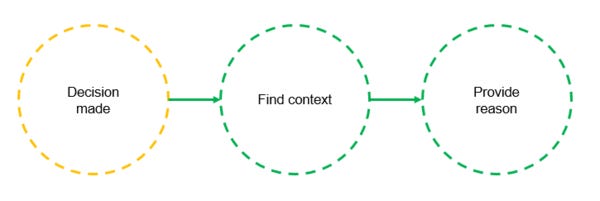

One helpful experiment is to think of any capital city. Think of one now? The process of being asked that question and then settling on an answer feels like it goes something like this:

This looks like free will. And if I asked why you chose that city, say Amsterdam, you’d say something like ‘I went on holiday there last year’ or ‘I was born there’.

On closer inspection, this was not so rational: you probably only thought of a couple of cities (not the 100+ you know), you don’t see what you did to deliberately choose between them, and then you made a decision. We are entirely in the dark about every decision we make because the process is so opaque. Worse still, many studies have shown that researchers can predict the decision you are going to make by up to 10 seconds(!) before you make it (yes, even if you changed your mind at the very last second).

What, I think, really happens in the brain is more like this:

This process of us unconsciously making a decision and then our brain rushing to justify this reason aligns closely with Julian Jaynes’ book The Origin of Consciousness: “Logic is the science of the justification of conclusions we have reached by natural reasoning. My point is that consciousness is not necessary for such natural reasoning to occur. The very reason we need logic at all is that most reasoning is not conscious at all.” The critical suggestion here is that we can live our lives, to a great extent, without consciousness—it’s not necessary.

The most extensive critique of this way of thinking is that the ‘I’ comprises conscious and unconscious actions and desires. I might decide but will be unconscious of the reasons why (as is often the case with love). But, the decision appears to emanate from within me—I, therefore, take ownership of this. Yet, the ‘I’ that I see myself as doesn’t take responsibility for my heart beating or the cadence of my breathing. I don’t consciously think of these either. The ‘I’ that is me is conscious—it’s typing these words.

‘I’ see myself as relatively successful (as most of us do). However, our perspective on success and failure is telling and helpful in this context.

In 1979, Jay Pinkerton broke into Sarah Lawrence’s home, raped and subsequently to stabbed her 30 times, and then raped her again post-mortem. Her children were asleep down the hall. A year later, Pinkerton committed a similar crime, for which he was caught and sentenced to death. The offence is horrendous in every way.

Pinkerton was 17. On a human level, we must ask what childhood did Pinkerton have to culminate in such terrible crimes. Do we hold Pinkerton responsible for what he did? Our criminal justice system is built around the premise that people have the ultimate choice over their actions. This implies that if we were in the same position (perhaps outside of Sarah Lawrence’s home), with the same lived experience, upbringing, genes, and education, we would have made a different decision and not gone in. Of course, if we were to trade places with Pinkerton atom-for-atom, memory-for-memory, we would have acted in the same way. The situation dictated his actions.

In stark contrast, Jeff Bezos attended Princeton, began his career in fintech, and then moved to a hedge fund before starting Amazon in 1994. Since then, he’s ridden the internet wave and is now the richest man in the world. Can we hold Bezos responsible for his success, too? As with Pinkerton, we must ask, what kind of childhood did Bezos have?! You can be comforted, too, to know that if you were to swap places with Bezos, again atom-for-atom, your outcomes would be the same.

So, is this a fatalist perspective if you and I don’t have free will? Should we loaf about and see how the world unfolds? In short, no. This way of thinking does not detract from the significance of every proactive move you’ve made in your life. You have an excellent opportunity to do what you can with what you’ve got (and you’ve been given everything you have).

If you’re a proactive, energetic, and sociable person, double down and be all those things. There is path dependence in getting you to be that person, so you (modestly) can’t say ‘I did this’, but you can say ‘I’m lucky to be the type of person who could do this’. Similarly, when you see someone who has acted poorly, they invite more compassion—they would never have chosen to be unhappy (or a crook). Moreover, they could never have chosen, even if they wanted to.

So, this is my two pennies on free will. Let me know your thoughts. I think I might turn this into a longer piece as it felt a little constricted!

Have a great week

Hector