Equilibrium (Part 2)

So, all being well, I’m still on my bike, on a hill, in Slovenia, offline! Part two of these thoughts on the media equilibrium is below, and part one is here.

Have a great week!

H

Authorities with information have mobilised millions of people and silenced them. As I mentioned, we saw the exercise of control most extraordinarily during the World Wars. Industrial technology awarded centralised authorities with new powers. Small groups of people (governments) battled on a global scale. The wars are landmarks in the use of information to control the public. Edward Bernays said in 1928: "[World War I] was an extraordinary state accomplishment: mass enthusiasm at the prospect of a global brawl that otherwise would mystify those very masses, and that shattered most of those who actually took part in it. … the worlds of government and business were forever changed". At the time, and in the following decades, Authority spoke to the public, and the public acted.

By controlling the narrative (and the people), Authority maintained its power over an unstable society. To extend its own reach, Authority incubated innovation. It seeded the printing press, the radio, television and the internet.

Soon, however, the unwanted information began to circulate. Each phase of broadcast innovation had its battle with Authority, as governments sought to maintain their monopoly. Goebbels's call 'to commit to the flames the evil spirit of the past' (burning books) in Nazi Germany in 1933 demonstrates the threat that the printed page had over Authority. The underrated film The Boat That Rocked tells the story of a pirate radio station battling British prohibition by broadcasting from international waters in the '60s. Newspapers, too, are political pawns. As Prime Minister Orban has firmed his rule of Hungary, the largest opposition papers (Nepszabadsag in 2016, and Magyar Nemzet in 2018) have closed. Orban's allies have continued to acquire media and advertising outlets – outlets now directed at supporting government policy. Even today, authorities seek to control the narrative of society.

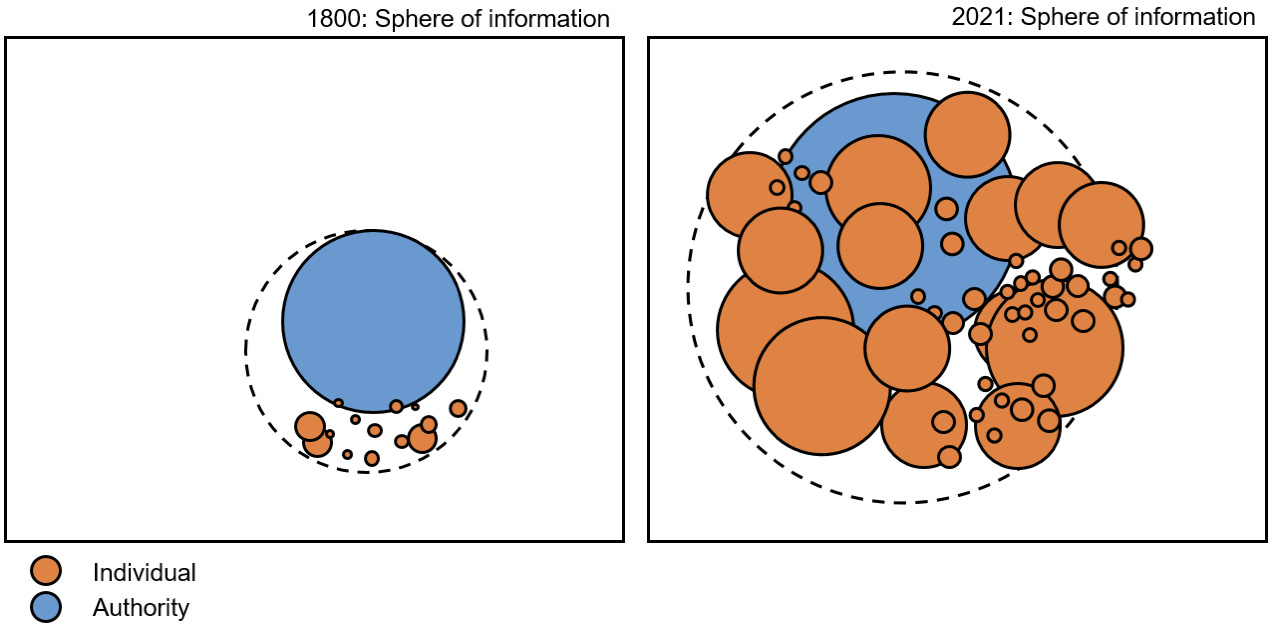

There's sometimes talk about the inversion of power, but this isn't quite right. The individual won't become more powerful than the state, with a standing army. Individuals are gaining relative influence within the sphere. The sphere is growing, and the state no longer controls the narrative. In states that have open borders, it's unfeasible to pump out enough content to maintain informational dominance.

Those who hold information have power. They are positively correlated. The nuance is that power falls to those who can distribute their message to others. Propaganda machines, enabled by radio and newspapers during the wars, muted counter-opinions. The ability to take a concept and spray it out onto the world, or—today—to one's followers, is powerful. The monopoly on information is gone (and it will never return). So too, has the monopoly on distribution. The message and the medium are entirely decentralised. This equilibrium in information creates opportunities to leverage influence like never before.

So we can frame this equilibrium as a great empowerment. Of course, the state's ability to organise and disseminate its message has increased, too. With Cambridge Analytica in tow, it uses Facebook Pixel, MailChimp and Twitter. Yet, there is no relief in the sphere from the content output by the individual creator. The sphere has grown, as has the power-hose in it, yet there are many more motivated individuals than authorities.