Ulysses: A Glimpse of Insanity

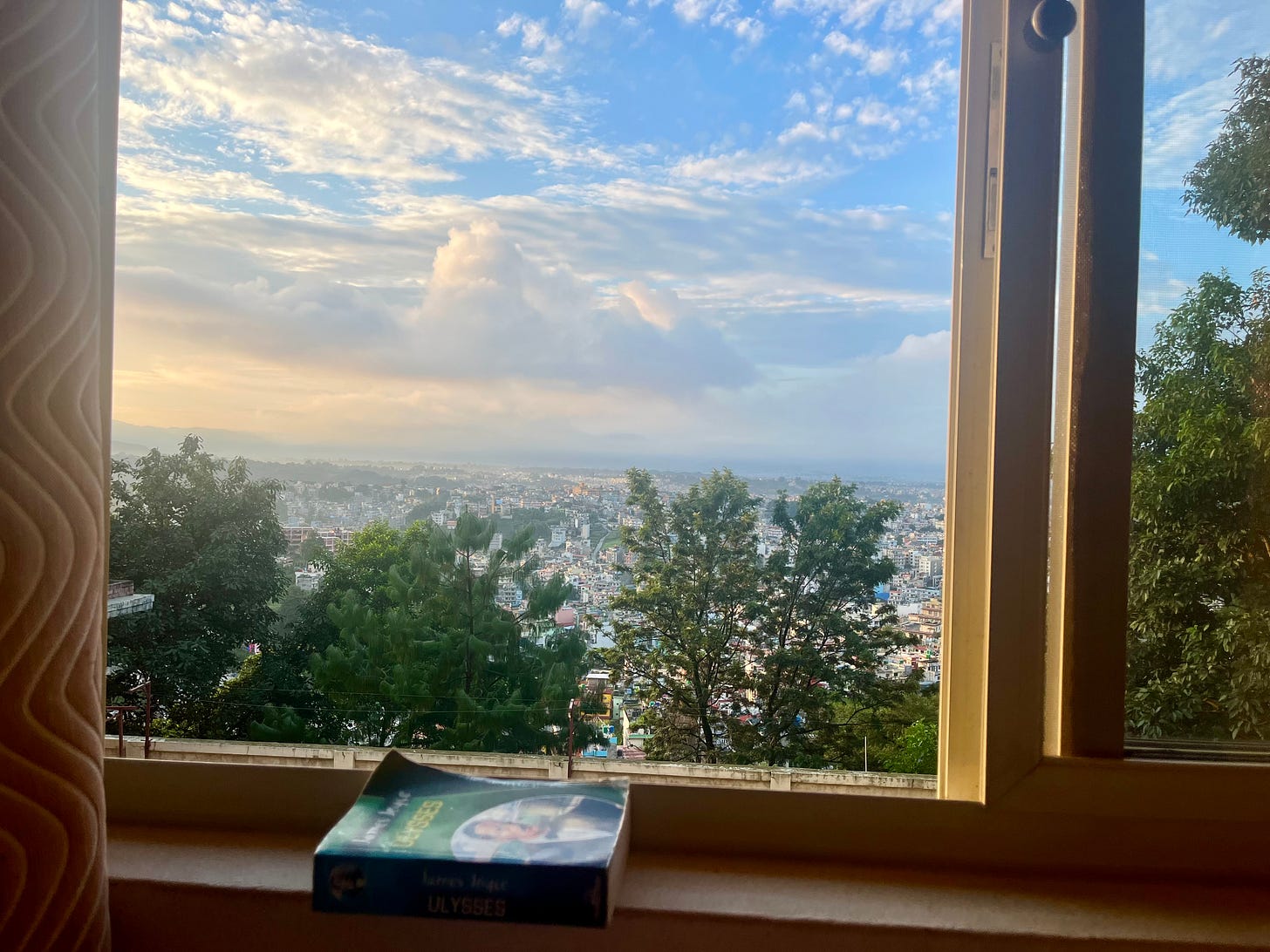

📍Kopan Monastery, Kathmandu, Nepal (Issue 199)

It was 2008. Five of us went hiking to complete our bronze Duke of Edinburgh award. We were not a cool group: not one of our families owned a hotel in Positano, none of us went to parties in London, we listened to The Fratellis, and probably we didn't know what Supreme was (something we learned in divinity class, certainly not a brand). It was the era of the PlayStation Portable and the iPhone had just been released. We were fourteen-years-old, innocent and inexperienced: Olly, who we'd nicknamed the goose because he resembled one with downy white hair; Michel, who had great gleaming braces; Rob, the tallest of us; Hector Hughes, the shortest (a late bloomer); and me (equally late to bloom!).

My memory is hazy, but we met at a forgettable grey army camp in Dartmoor, in Devon and climbed onto the moors. We camped at night in the tents we carried, and returned, after perhaps a week, sodden. It's exposed up there: the wind blows in from the Atlantic and there's almost no vegetation to break it in—simply featureless moss-green rolling country, patches of low gorse and acres of peat bogs.

For days, in our shrill, unbroken voices, we talked about the weather.

The weather was very bad. The wind carried tremendous heavy clouds to us from the Atlantic, which surrounded and blinded us. It never rained, and yet the moisture in the clouds made everything wet. The clouds moved around us like big grey fish—as if swimming, slowly but resolutely; you could watch them rolling up the hillside and inevitably engulfing us, as if eating us up. Our raincoats became drenched inside and out; our hands and noses dripped onto our maps.

We were often lost. Our OS map would flap relentlessly in the gusting wind. We’d search the horizon physical features from which we could orientate ourselves. All five of us, huddled around a map like penguins staying warm, would together stare at the middle-distance searching for a gravel pit, a scree slope, a bouldery outcrop, or maybe some marsh or bracken or an evergreen coppice. If lucky, we'd spot a church with a steeple in the valley, or walk past a phone box or perhaps a pylon or triangulation pillar. We’d take a bearing, rotate the map 65 degrees, and look up again: but the hideous cloud blanket would have returned, and our gravel pit or cops would have disappeared entirely—magicked away!—poof! The precious pylon, our anchor to reality, was replaced by impenetrable grey mist—gone, it seemed, forever.

But, occasionally, there would be a gap in the clouds, and our visibility would jump from five metres to a kilometre. It would feel like we're coming up for air. We could breathe! Suddenly, we would be blessed with a broad vista to orientate ourselves. And we'd see that long line of pylons to our left and a triangulation pillar to our right and a church with tower on a hill! We'd find our location instantly and trudge along the tiny red-dotted footpath towards our campsite.

I mention all this because I got the same feeling when reading Ulysses: I'd wade through page after page of impossible-to-penetrate prose. I'd be lost, disoriented, somewhat drowning and wet with sweat. And then, as if blessed, the fog would clear, and I'd regain my orientation and enjoy a few pages of delightful narrative. But then, slowly, as if I was sinking into Joyce's confused subconscious, I would begin to lose my way. The clouds would roll in from some Atlantic storm. The landmarks of the plot would disappear, and I'd be left bewildered and grasping for some muddy footpath of a story.

For example, I'd stumble into the following (page 621):

He rests. He has travelled.

With?

Sinbad the Sailor and Tinbad the Tailor and Jinbad the Jailer and Whinbad the Whaler and Ninbad the Nailer and Finbad the Failer and Binbad the Bailer and Pinbad the Pailer and Minbad the Mailer and Hinbad the Hailer and Rinbad the Railer and Dinbad the Kailer and Vinbad the Quailer and Linbad the Yailer and Xinbad the Phthailer.

When?

Going to dark bed there was a square round Sinbad the Sailor roc's auk's egg in the night of the bed of all the auks of the rocs of Darkinbad the Brightdayler.

Where?

What am I to do with that? Is it nonsense, or am I too stupid to get it? I am not alone in my confusion. Even Jung found Ulysses challenging:

"The seven hundred and thirty-five pages that contain nothing by no means consist of blank paper but are closely printed. You read and read and read and you pretend to understand what you read. Occasionally you drop through ann air pocket into another sentence, but when once the proper degree of resignation has been reached you accustom yourself to anything. So I, too, read to page one hundred and thirty-five with despair in my heart, falling asleep twice on the way." – Carl Jung, in a 1932 review

But, for an aspiring novelist, it can be rewarding. Rewarding because it shows (a) that you can be experimental with your writing and (b) there are many different ways to write a successful book. Indeed, it was selected as the greatest novel of the twentieth century! Huxley, although he said it's one 'of the dullest books ever written', conceded that Ulysses is a 'a kind of technical handbook, in which the young novelist can study all the possible and many of the quite impossible ways of telling a story…'

I can’t help but feel I am not yet capable of understanding the book, and that there is a seed of brilliance buried inside, beneath those densely filled pages of crazed gibberish. I expect a second or third reading to uncover the magic I have hopelessly missed. After all, Orwell loved the book—he read and reread it for months—and recommended that his various girlfriends read it. (Poor them!). In 1934, he wrote to his girlfriend: '[Ulysses] gives me an inferiority complex. When I read a book like that and then come back to my own work, I feel like a eunuch who has taken a course in voice production and can pass himself off fairly well as a bass or a baritone, but if you listen closely you can hear the good old squeak just the same as ever.' I agree: often, the conversations between the characters are so natural, so fun, that 'normal' conversations in other novels feel dry and a little dead.

Moreover, the majority of the book is an investigation into Leopold Bloom's subconscious, and this is interesting.

It's very difficult (impossible, perhaps?) to glimpse another person's subconscious meanderings. Our inner musings, our raving and jabbering, are ours alone. Writing now, I have only a light perception of my self-talk. I see the sign above me: Avocado Cafe; my waiter has bleached his hair, a chef is banging and hacking a pineapple to bits in the adjacent room, and thoughts from my dreams last night return to me. I'm booking a taxi for tomorrow; the waiters hug, brothers? A crowd cheers at the long table, shouting Mister, mister, mister; my glass is empty—shall I get more water? Why is that table so loud? Hard chair. They are wearing Lions International T-shirts… etc. etc. etc.

The subconscious! When you let it go, it just rambles on. And this is what Ulysses does. You start with lucidity, that flash of plot, a moment of sanity, but very slowly, Joyce takes us with him, not really holding our hands but perhaps pushing us into the subconscious—a place unrestricted by the phenomenal realm. Beyond logic and maths, and after gravity. This is an exciting place to be! It might not be a story with a plot, it might not be absorbing the whole time, but it is a new place, a place I haven't visited before; but, like the peat bogs and the wind and the driving rain in Dartmoor, I’m in no particular rush to return.

This month (September) Hector Hughes and I are reading Homer’s Odyssey. Please join us! Read more about our book club and see the full list here.

Have not embarked on JJ. But find Huxley random too and am taking a break for a bit of Boyd !!