#93 | So fast, with so little

“The very least you can do in your life is figure out what you hope for. And the most you can do is live inside that hope. Not admire it from a distance but live right in it, under its roof.” — Barbara Kingsolver

“Happiness is when what you think, what you say, and what you do are in harmony.” —Mahatma Gandhi

We live in a world containing unthinkable — and often unreported — suffering.

Perhaps 100 billion non-human animals are eaten by human animals every year.

Thirty-eight million children are at risk of brain damage yearly because of iodine deficiency, an entirely preventable condition: it costs ~£0.05 a year to fortify a child's salt.

Two million older people live alone in the UK, many of whom are isolated from family and community.

Modern society has progressed quickly in some areas but stalled in others. It's easy to get numb, apathetic and disconnected when there appears to be so much to do.

However, among these tragedies, it's vital to recognise how unlikely it is that we live today (of all potential days) and how early we are in the grand sweep of time. With these in mind, we can be optimistic about what humans might achieve in the future; we are still a child of a future adult civilisation.

Ultimately, our descendants will look back not at our *backwardness* but at the complexity of our society that we somehow developed with the very basic (and human-designed) tools that we have today.

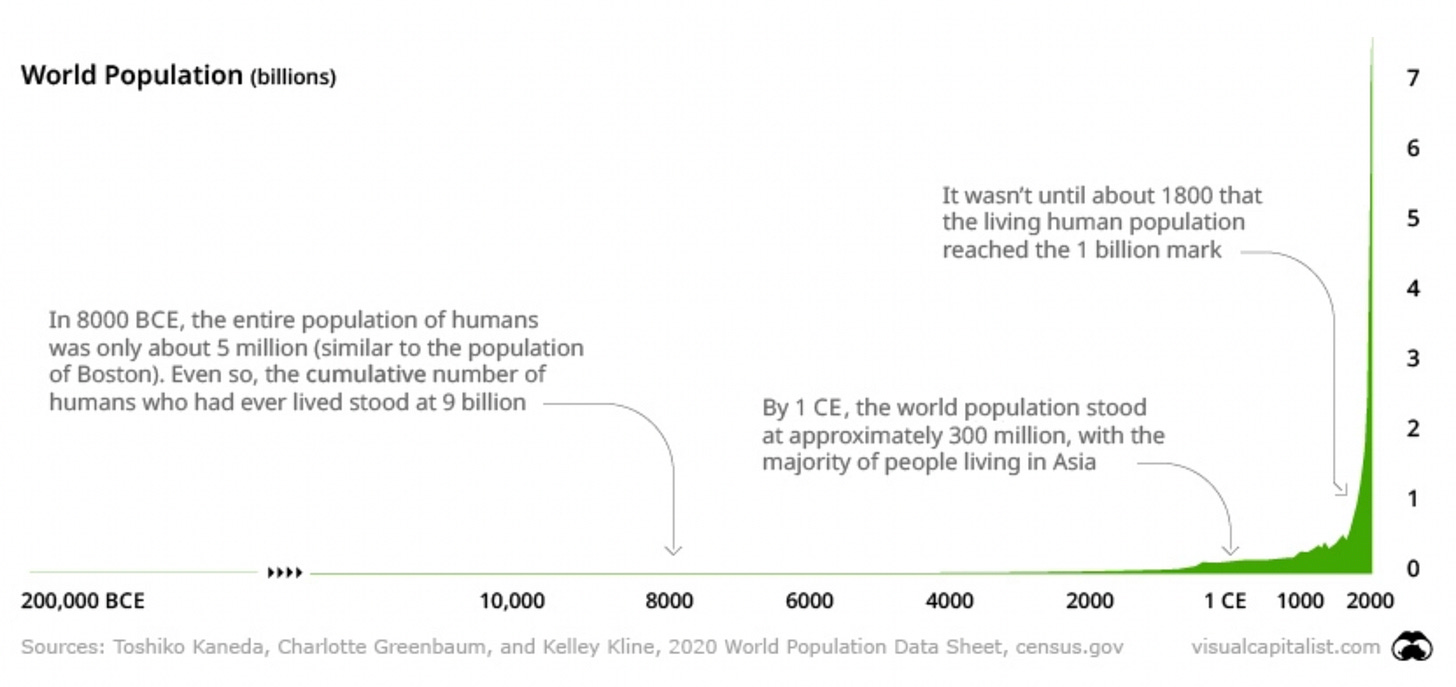

Taking these points in turn, it's absurd that we live now: If we look at just human history, 117 billion people have ever lived, so across all of our human ancestors, we have a 7% chance of being alive today. Human history is relatively short; 200,000 years seems to be day one, according to most articles I've read. It took a full 190,000 years for the first 8 billion people to exist in total. Now there are 8 billion alive today.

Population, as we know, has recently exploded. Until 8,000 BC, the world's population was only 5 million — it's now 1600x that. Let's assume humanity survives for another 200 thousand years (conservative given the average mammal lives for 1 million years). Let's also assume the world sustains 8 billion for the remainder of this time (which appears sustainable though conservative, are increasing the earth's carrying capacity with technology); then 10^15 humans will exist in this 400 thousand-year period. Therefore, the chances of being alive today is 0.0005%. (The fact that we have no idea how much longer humans will continue makes analysis like this somewhat limited. Nevertheless, it's helpful to point out that it's an unusual time to be alive.)

Moreover, alongside this population explosion, there has been a corollary rise in the economy. Nick Bostrom writes in Superintelligence that the growth rate of our civilisation's economic productivity and technological capacity is booming. Referencing Robin Hanson, an economist, Bostrom writes:

a characteristic world economy doubling time for Pleistocene hunter-gatherer society of 224,000 years; for farming society, 909 years; for industrial society, 6.3 years.

Bostrom says: 'If another such transition to a different growth mode were to occur, and if it were of similar magnitude to the previous two, the world economy would double in size about every two weeks.' Wild to think, perhaps, but imagine telling a hunter-gatherer that the economy would double multiple times in their lifetime.

These exponential truths have been widely written, and we live amongst them. There are many more exponential facts I could throw up (I include two graphs to show the ferocity of the liftoff). Yet there is a logical conclusion that we are very early to the exponential party; it's only just begun. And far from being a developed and prosperous world, we're only recently, in the long-run view, leaving the flat agricultural period of not much changing from millennia to millennia.

Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel (also called the infinite hotel) is a conceptualisation of a hotel with infinite rooms. For every new guest who arrives, you move a guest from Room 1 to Room 2, and the guest from Room 2 to Room 3, and so on, and welcome the new guest to Room 1; you can do this infinitely. Similarly, if a new floor of guests arrives by coach, you can move the guests from the Ground Floor to the First, and the First to the Second, and put the new guests in the rooms on the ground floor. This can be done infinitely, with an infinite number of coaches arriving!

In the infinite hotel, even if you're in some absurdly high room number, say Room 10^30, you are still so early in terms of all the infinite room numbers in the hotel. You're always right at the very start of the potential of the entire hotel, and even if the Management had to move you (the air-conditioning was faulty) to Room 10^800, you'd remain right at the start of the list of all possible rooms. This list would be infinitely long! It's impossible to fathom this hotel's scale. Yet, when we're looking at our long history of humanity, we're inconceivably early compared to the infinite potential of our species.

I recently walked around the Pergamon Museum in Berlin and through Ishtar Gate, the blue gates of Babylon. Later, I stared into the marble eyes of Julius Caesar. When meeting marble Ceaser, who died 2,062 years ago, I did not remember that Roman society's life expectancy was just 33 years, just 40% of ours. Nor did I consider how they barbarically put slaves to fight in coliseums built by enslaved people. Instead, I thought, in awe, how much the Romans and Babylonians achieved with such limited technology. In 200 millennia, with all that history in between, how much will humans distinguish between the Roman and American Empires? Less than we might like to think!

In 1950, Alan Turing published an article in the journal Mind, titled 'Computing Machinery and Intelligence. The paper starts with the famous proposition, 'Can machines think?', and ends with a chapter on Learning Machines. In this final chapter, Turing suggests:

'Instead of trying to produce a programme to simulate the adult mind, why not rather try to produce one which simulates the child's? If this were then subjected to an appropriate course of education one would obtain the adult brain.'

Turing's idea of us creating a child that learns, rather than leaping to build a fully functioning adult, is one conception of developing intelligence beyond our collective human capacity. Yet it has broader implications in our being unusually early, too.

As a society, we are a child, limited to human-conceived tools. When surrounded by suffering, we get frustrated at the sluggish improvement in people's lives. When will we eliminate extreme poverty and remedy global warming? However, I think we can be kind to our ostensibly cruel and intractable civilisation, considering how much has been done so fast with so little.

My week in books

This is the first time I've gone deep on one author and batch-read their work; it's a great way to read (Tyler Cowen says:

"I advocate reading books in cluster – the author can be the clustering factor, it can be the topic, it can be the historical period – but you really get into a person’s mind if you re-read everything they’ve done within the span of a few weeks or months...")

Peter Singer is an Australian moral philosopher who provides many ethical frameworks behind the Effective Altruism movement. His premise is that we all have a moral obligation to give money (or time) to alleviate suffering and that not all charities (or causes) are equal. Some charities can be thousands of times more impactful than others. I'll include a quote for each, as they all discuss the same general topics.

Practical Ethics. "Helping is not, as conventionally thought, a charitable act that is praiseworthy to do but not wrong to omit. It is something that everyone ought to do."

The Life You Can Save. (Check out the affiliated organisation, too). Start with this book if you want the best way into his thinking.

The Most Good You Can Do. "Living a minimally acceptable ethical life involves using a substantial part of our spare resources to make the world a better place. Living a fully ethical life involves doing the most good we can."

Famine Affluence and Morality. This may be the most impactful piece of work Singer has produced; the essay (in this book) with the same title is referenced everywhere.

Why Vegan? A very compelling book, and I'm looking forward to reading Animal Liberation, also by Singer. Regarding non-human animals: "The question is not, Can they reason? nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?" Of course, all animals can suffer; therefore, we shouldn't be eating non-human ones.

Hector Hughes and I are having a monthly book clubby-thing, where we read a book a month: This quarter, the topic is 'war'. Next up we're reading On War, and in September, it will be The History of the Peloponnesian Wars. Reply to this email to join us.

Keep signing up

(My brother) Wandering Lex's first-ever album release party!!!! It's on Friday (August 12) at Bush Hall, in Shepherds Bush.

It's being transformed into an island for the evening (samosas, watermelons and sand etc.), and they will be performing a soon-to-be-released full-length album made in Kenya! Listen to a flavour of the island sounds.

Book tickets (£16.80) ASAP (they are selling out). I can't wait to see you there! Link: https://dice.fm/event/gro9a-a-night-on-the-island-12th-aug-bush-hall-london-tickets

Live well,

Hector