#144 | Agree to disagree

“Some of us think holding on makes us strong, but sometimes it is letting go.”

— Hermann Hesse

"We're all going to die, all of us, what a circus! That alone should make us love each other but it doesn't. We are terrorized and flattened by trivialities, we are eaten up by nothing."

— Charles Bukowski

We all know the world is increasingly polarised, the BBC tells us.

While global warming is cooking us from the outside, many have boiled over from within at a mid-wit on Twitter or misleading click-bait on the Daily Mail. "Can you believe they wrote this?", "who elected these idiots?" and on we go. But we aren't as polarised as we're told, nor is it necessarily bad for society. Disagreement, net-net, enables progress. Homogeneity paints the world grey.

Polarisation, the narrative holds, is why our politics doesn't work. It's why politicians never get anything done. It's why we watch Fox or CNN but never both. (Each describes a different country). It's why Brexit can't be discussed at Christmas.

And the one thing that everyone agrees on is that we disagree more. Hell, the other side doesn't or won't or can't understand us. The other side doesn’t "get it" because they are too stupid; they watch CNN, listen to Farage, or don't listen to Trump. Whichever way we slice the pie, there are those who (correctly) agree with me and those who don't. The dynamic leads to gridlock. And fury.

"The most dominant political trend", says one BBC commentator, is that "people are more embedded in their own camps." These camps are ideological. And this is partially because our news comes from newsfeeds, which present content that confirms our biases and keeps us skimming. And while there is good evidence of this happening, we could also point to other data demonstrating these "camps", while different, are getting closer together.

We're not as polarised as we think. Nor are we nearly as divided as we have been historically.

A new film about Napoleon comes out in November. I can't wait to watch it. He soldiered as France turned upon itself in the decade from 1789. As heads rolled, he took advantage of the chaos of the revolution. Napoleon installed democracy and then incrementally removed it. In the end, he became Emperor for life with an heir. He was exiled and then returned and then exiled again. Not, all in all, very democratic. I would argue, with irony, that we can describe Napoleon's time as having "increasing polarisation". Similarly, if we think back to Europe for almost the entire last century, with two World Wars and then a Cold War, which split the continent: there were disagreements about how the world should look.

We are on a hiatus from those fundamental disagreements.

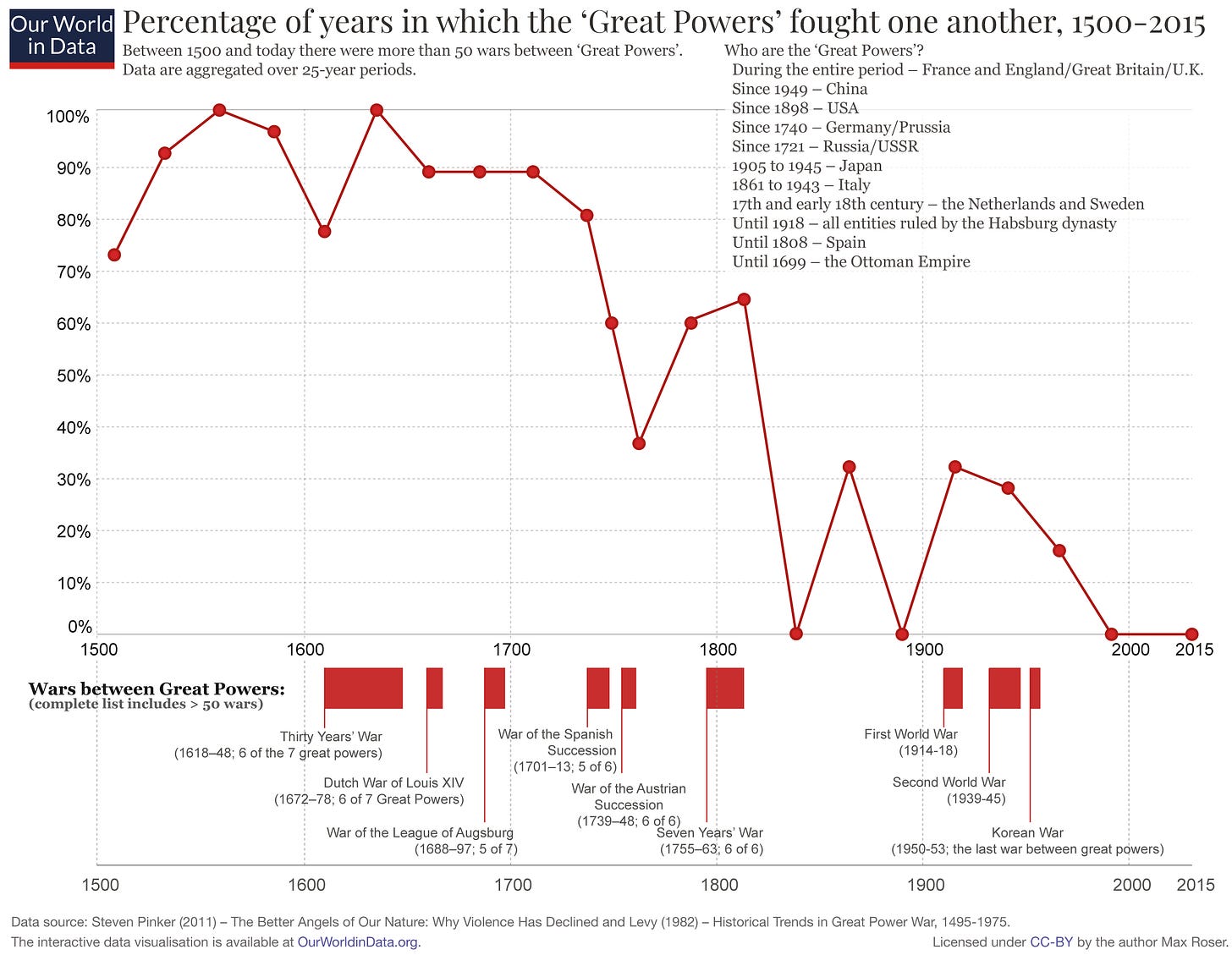

There is a lot of evidence of us all agreeing. The best proof is that most countries are not at civil war. Still, fewer are actually at war with one another. The graph shows the number of wars between the great powers. This has dropped precipitously.

Generally, in Britain, we agree more culturally. 17% say it is "very important for being truly British that someone has been born in Britain", down from 48% in 1995. Similarly, in 1995 52% agreed that "Britain is better than most other countries"; today, 34% believe this. 45% say that "equal opportunities for Black and Asian people have not got far enough", up from 25% in 2000.

We are increasingly liberal and increasingly agree on important liberal questions.

Internationally, Stephen Pinker provides the following evidence: Google searches for racist, homophobic and sexist jokes fell by 80+% between 2005 and 2017. Pinker writes: "contrary to the fear that the rise of Trump reflects (or emboldens) prejudice. Private prejudice is declining with time and declining with youth, which means that we can expect it to decline still further as aging bigots cede the stage to less prejudiced cohorts." Similarly, Pinker writes that better-educated people are more liberal. Therefore: "In many Middle Eastern and North African countries, more than three-quarters of the people over 65 are illiterate, whereas the rate for those in their teens and 20s is in the single digits. The [world] literacy rate for young adults (aged 15 to 24) in 2010 was 91 percent." This is bullish for general liberalisation.

Today, rather than going to war (with Ukraine a tragic exception), we disagree about whether we should be within or without a political union and censor the books kids read in schools.

"A dynamic force seems to be drawing first Western society, then the rest of the world, toward a state of relative indifferentiation never before known on earth, a strange kind of nonculture or anticulture we call modern." - Rene Girard

So today, perhaps, we see the most extraordinary homogeneity of ideas, rather than overwhelming division. Maybe there are not too many revolutionary ideas, but too few. It's not that we are so far apart; instead, we are on top of one another and unable to conceive of a dramatically better world. There is a cost to homogeneity. Just as we are concerned about the drift towards civil war, we should be equally worried about living in a world where everyone agrees.

My week in books

The Man Who Cycled The World by Mark Beaumont. This is an awesome story; he gets round the world in 270 days — impressive. Years later he does it in 79! Thanks to George for the gift 🔥

Live well,

Hector

P.S. The "♡ Like" button looks insignificant, but it indicates Vertigo’s worth to visitors. Please don't hesitate to show your support. Thank you!

Fantastic article. Hector!

I believe that the subject that divides the world the most at the present time is RELIGION.

Terrific read x