#130 | GPT's satanic mills will be worth it

Lessons From Revolutions

"You talk as if a god had made the Machine," cried the other. "I believe that you pray to it when you are unhappy. Men made it, do not forget that. Great men, but men. The Machine is much, but not everything." ― E.M. Forster, The Machine Stops

"What an astonishing thing a book is. It's a flat object made from a tree with flexible parts on which are imprinted lots of funny dark squiggles. But one glance at it and you're inside the mind of another person, maybe somebody dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, an author is speaking clearly and silently inside your head, directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people who never knew each other, citizens of distant epochs. Books break the shackles of time. A book is proof that humans are capable of working magic." ― Carl Sagan, Cosmos

There has never been a better time to read history. There is more of it than ever (ha). And, when living through moving history, reading reminds us times have moved swiftly before. After all, your ancestors survived the agricultural and industrial revolutions. We're lucky, I think, to be up-ended by the information and intelligence revolutions.

Even so, it will be uncomfortable. We're accustomed to 2% economic growth. We're used to innovation at the temporal pace of people, not machines. Our economic booms reached a thumping once-a-decade rhythm. Dramatic political events, wars and revolutions, now happen overseas; not at home. Our politics appears to be increasingly polarised… but not as polarised as the warring sides of a civil war.

Today’s relatively comfortable rulebook is being rubbished. Why? The price of intelligence, until now our most valuable and scarce asset, is heading to zero. The pace of everything will speed up to that of machines. Life, therefore, is about to get interesting.

Walking with Hector in Stow-on-the-Wold this weekend, I picked up a copy of Progress and Poverty by Henry George. Published in 1879, Progress and Poverty looks at the previous century of industrialisation. George recognises the "association of poverty with progress is the great enigma" of his times. He asks how progress is possible (economic growth) while suffering remains (child labour, toil and sickness). Today, George's enigma remains ours:

"The new forces, elevating in their nature though they be, do not act upon the social fabric from underneath, as was for a long time hoped and believed, but strike it at a point intermediate between top and bottom. It is though an immense wedge were being forced, not underneath society, but through society. Those who are above the point of separation are elevated, but those who are below are crushed down."

Our new forces, our LLMs and GPTs, might well split society too.

The first country to industrialise was Britain, and 1776 was a significant year. In 1776, James Watt built his first steam-powered engines in small towns like Tipton, in the West Midlands. In the same year, Richard Arkwright's textile factory was burned to the ground by his workers, who were furious about his new water-powered machines. Using machines, Arkwright no longer needed 400 workers and paid those who remained less.

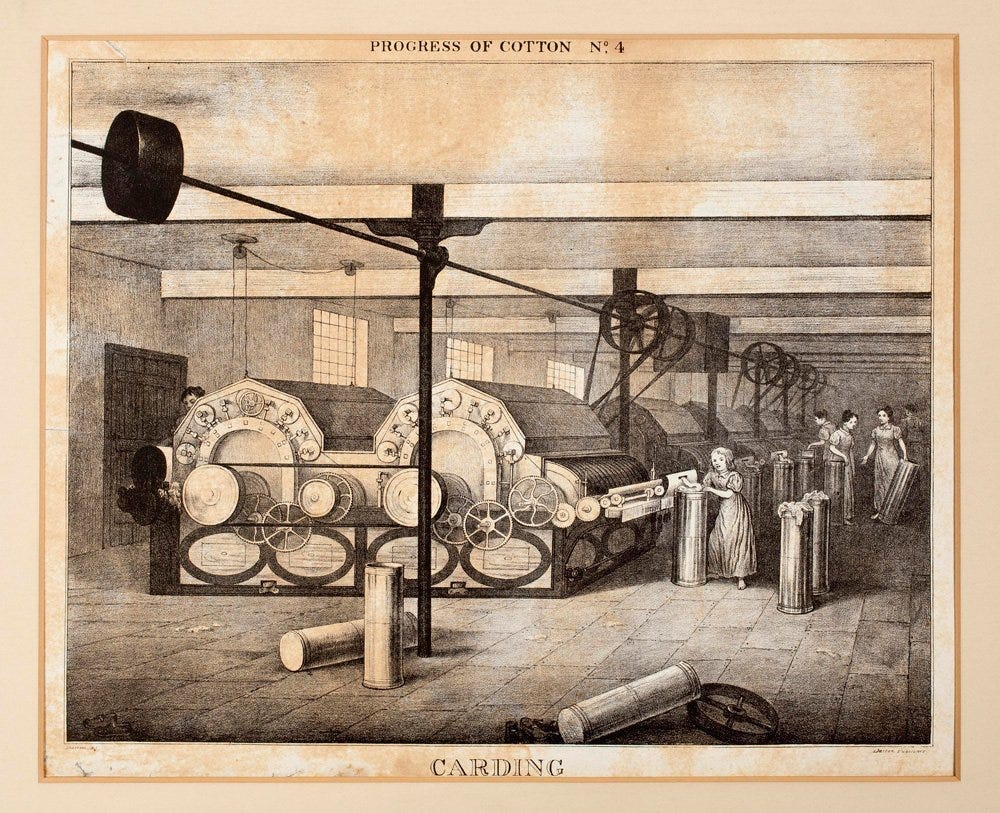

Machines replaced humans. "The profits arising from the machinery of Sir Richard Arkwright were so considerable," said Sir Robert Peel three decades later, "that it frequently happened… that the machinery was employed for the whole four-and-twenty hours." Workers (in 1776) submitted a petition to parliament against mechanisation. The House of Commons threw it out and backed industry at the expense of workers. Economic growth, as it often does, took precedence. Who could compete with twenty-four-hour labour? William Blake points to the "dark Satanic mills"; working non-stop, filled with half-starved children, looming like cathedrals over Liverpool, Birmingham and Leeds.

Beyond Tipton's factories, the industrial revolution was felt in England's fields. Moreover, the agricultural revolution, a different and slightly earlier beast, relied on knowledge, technology and specialisation (but not machines at the outset). New agricultural technology could reduce the number of farm workers needed by 90%. One such example was the Rotherham plough, patented in 1730. It replaced teams of horses and men with only one of each. In the century to 1800, farmers grew farm yields by 250%. Food production kept up with remarkable population growth.

Horses replaced men, and later, machines replaced horses. The lot of agricultural workers worsened. Villages became de-populated for lack of work; people headed into towns to work in Blake's Satanic mills. By 1800, only 30-35% of the workforce worked in agriculture, down from 80% a century before (today, it's 1.5%). And from 1830, the Swing Riots spread across South West England, where workers destroyed threshing machines, which became common across the countryside and signalled the destruction of the traditional peasant way of life.

These dramatic changes have, on balance, improved people's lives in the longer term. In Stephen Pinker’s Enlightenment Now (a book I’m reading and loving), he demonstrates how much better life is today, since the Enlightenment: The world’s wealth has increased two-hundred-fold in three centuries. Life expectancies have nearly doubled; today, no country has a life expectancy lower than Sweden in 1860, which, at 45, then had the world's highest life expectancy. Since 1970, our population has increased from 3.7bn to 7.3bn, and the number of people living in extreme poverty has fallen by 75%. Every day, the number of people in extreme poverty falls by 137,000. These are the irrefutable fruits of modernity.

But in transitional times — in moving history — we’ll see political instability, resistance, panic and, frankly, considerable suffering. Yet, would any of us want to put the breaks on industrialisation? Centuries later, it's improved our lives, and the lives of almost everyone on earth. The alternative paths into stagnation would have likely been worse, and to re-wind to pre-historic times impossible. (I say this, conscious of and subsumed by hindsight and survivorship biases).

“Industrial vs. intelligence” is not a perfect analogy: We don’t yet know the impact of GPT. Also, it took a century to industrialise a nation. It will take less time to feel the intelligence revolution's impact. Different strata of society are affected at first, and the welfare state exists today, which may cushion the blow. Many are already competing with, or otherwise benefitting from, LLMs. Whereas machines displaced physical labour in the 18th and 19th centuries, it is now the turn of the knowledge worker. Yet, in the long-run, it will likely be worth it.

My week in books

Why William Blake Matters by John Higgs. John is one of my favourite authors, and his biography of William Blake and Timothy Leary are both excellent. He is an optimist, and it comes through in his writing. However, start with his bio if you want to learn more about Blake.

The Machine Stops by E.M. Forster. A dystopian sci-fi where humans have instilled ever more autonomy in the god-like machine, which (spoiler) eventually stops working. Fascinating and relevant read.

A Brief History of Britain: 1660 to 1861 by William Gibson. I need to learn more about our history, and reading this book inspired this post. It's settling to know we've survived moving history and that, while new, this chapter is merely another chapter to an exciting time.

Live well,

Hector

The "picking up an old book while walking in the fields" is exuding Solarpunk nostalgia. It's interesting – perhaps one generation is too fragile to experience change without sorrow but new generations can live better in the future reflecting on how "hard we had it" without GPT.